Would you also like to benefit from our Travel Grants? Our applications are open all year! Find out more about the application procedure and criteria here

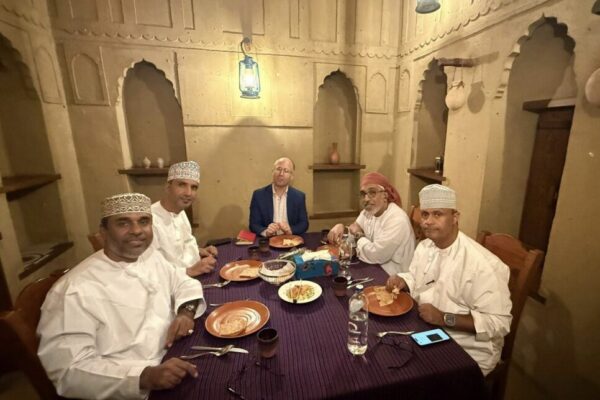

"I was amazed by the easy way I was introduced and connected to people. People were very welcoming and hospitable and offered my their time to explain about their customs, societal developments and history."

Prior to my trip to Oman, I had prepared an introduction on the purpose of my visit, highlighting that I aim to write an article for the magazine ZemZem, which aims to increase my understanding about the Middle East for a Dutch speaking audience in the Netherlands and Belgium.

I summarized the topic of the article as follows: ‘Oman is a Gulf nation at peace with itself, while enjoying good relations with the world. The country has experienced rapid developments in the fields of economy, agriculture, education, healthcare and infrastructure. How has Omani society managed to preserve its cultural heritage, local customs and unique traditions in an increased globalized world? What does modernity look like in Oman? How is Oman’s society successful in maintaining social peace, co-existence and mutual trust in a polarized region?’ With this introduction, I managed to connect to various writers, clergymen and historians in Oman.

In addition to information gathered through desktop research, I had various contracts/entry points through my own network in the Netherlands. Finally, prior to my visit I was able to speak with Mr Rabbani on the annual LRF meet and greet, where he gave me some ideas on Oman. My prior knowledge of Arabic as well as the fact that I used to live in Yemen (and am married to a Yemeni from Hadramaut) allowed me to interact quite easily. However, I was amazed by the easy way I was introduced and connected to people. People were very welcoming and hospitable and offered my their time to explain about their customs, societal developments and history.

I stayed in Muscat for a few days and then travelled by bus to Salalah (13 hrs), where I stayed for 3 days and visited the Dhofar mountains and nearby Murbat. Back in Muscat, I visited several musea, Nizwa and Bahla, where I was introduced to cultural centers, book shops and writers gatherings. The main lessons I took from all my conversations, observations and visits is that Oman is acountry which has been exposed to much more external influence than you expect from the outside.

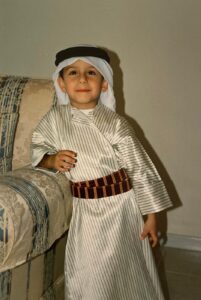

The fact that almost all (Omani) men walk in their white dishdasha and that customs and traditions are still very much valued doesn’t mean Omani culture is not subject to change. Although very different from neighbouring United Arab Emirates, Omani has historically been influenced by East Africa, Iran and Asia. Moreover, religiously the country has embraced a religious (Sunni, Shia, Ibadi) diversity in a different sense than other Gulf countries. In that sense, Oman shares more with Yemen than with neighboring UAE and Saudi Arabia.

That said, Oman developed very differently from Yemen and has for me been in many ways a contradiction to the country of Yemen that I know well: Oman has a well developed infrastructure, a stable economy, a cleaner environment, no poverty, functioning water and electricity services and most important of all, an effective governance system. The difference between now and Oman in the sixties is enormous: in that time many Omanis migrated to work in other parts of the Gulf, in Asia or in Zanzibar because of economic difficulties. Meanwhile, the country was weakened by internal rebellions.

This generation told me that they grew up in mud houses and explained that they experienced so much change in one generation that other countries experienced in five generations. Now how has this influenced Omani culture and identity? The change of traditional gender roles, people moving to the cities and the impact of labour migration (mostly from Asia) in addition to globalization trends (social media, cosmopolitan cultures) has impacted Omani culture and identities and has weakened social cohesion.

At the same, Omanis have (re) embraced their traditions by re exploring their history, culture and identity.

“My most valuable lessons, deepest insights, and best connections were established through other people”.

Last September, I traveled to Cairo to take part in an international workshop focused on building prototypes for natural ventilation in the self-built neighbourhood of Ard al-Lewa. It felt like a full-circle moment: back in 2017, during a university trip, I had studied Egypt’s traditional systems of natural ventilation and explored how these could be reinterpreted in a contemporary context. Returning years later to work hands-on, building physical prototypes and testing ideas within a real urban environment, was an opportunity I couldn’t miss. The workshop began with a city tour, offering us a layered view of Cairo’s social and urban fabric. It sparked lively conversations between Egyptian and international participants, revealing how deeply history shapes daily life. In Ard al-Lewa, despite its density and chaotic appearance, traces of the neighbourhood’s agricultural past remain visible. Men and boys passed through the streets on horse carts, collecting recyclables or delivering vegetables to market stalls. There was a sense of community, everyone seemed to know one another, forming a tightly woven social network in the area. When we began conceptualising our prototypes, our main challenge was to design something that the local community could easily replicate.

This discussion changed how I think about design and social engagement. In many contexts, innovation istreated as a product to be sold, marketed, and promoted. But the Egyptian designers in our team emphasised a different model: here, you don’t need to “sell” ideas. If you demonstrate that something works and share how it’s made, people will adopt and adapt it themselves. All we needed was one successful prototype, planting the seed.

As the workshop progressed, we worked daily in CLUSTER’s open workshop space, right in the heart of Ard al-Lewa. Passersby often stopped to ask what we were doing, sparking spontaneous conversations and exchanges. Working on-site created an immediate dialogue between designers and residents. Over time, seeing the same faces each day built a sense of connection and belonging, even if only temporary. One other eye-opening moment came when theory met reality. Our initial idea was a simple windcatcher that could be mounted atop existing building shafts to enhance airflow. Yet when we went to install it, we discovered a far more complex roofscape than we had imagined, filled with pigeon towers, goat sheds, and improvised structures. Our neat hypothesis had to bend to the messy reality of lived space.

Adapting our prototype to fit this environment became as much a design lesson as asocial one: theory must always meet the ground with humility.

Would you also like to benefit from our Travel Grants? Our applications are open all year! Find out more about the application procedure and criteria here

'There is something special about being immersed in the language so intensely'

Thanks to the support of the Luftia Rabbani Foundation’s travel grant and a scholarship from Sijal Institute for Arabic Language and Culture, I was able to dedicate all summer to Arabic language and finishing the interviews for my doctoral research.

Whilst I have been in Amman for most of the last three and a half years, I have never been able to dedicate so much time to Arabic or had the means to do so. This summer has been a true gift – every day Sunday to Thursday – glorious Arabic. Whilst it was a shock to the system to study Fusha for the first time since 2015, it really has been a privilege to have such patient teachers who’ve helped me shift out of my Ammiyeh vocab into Fusha – although with many mishaps along the way.

This alongside the fact that Palestine and discussing Palestine has been at the centre of most of our classes and the lectures organised alongside the core curriculum, has meant it has been the perfect opportunity to think about how I’ll begin the final year of my doctoral studies and begin to write up about all the ethnographic encounters in the city of Amman as well as the Material Witnesses of Palestinian Exile that participants have brought with them to my workshops since 2023. Whilst my work focuses on visual culture, the lecture by Dr Ramzi Salti on Arabic museum and revolution sparked a desire to think more about the sound of Amman – something I’d love to come back to after finishing my doctoral thesis.

This summer, alongside another researcher based in Amman, we co-hosted a workshop together as a way to experiment with the different creative tools we use to explore exile and futurity. The workshop was centred on the figure of teta. The workshop space became filled with different Material Witnesses related to teta, and saw the creation of several poems which brought these objects to life in a whole new way. The affective relationship between visual culture, tetas and grandchildren in Amman took on a new material tangibility.

Alongside this I’ve also been able to conduct a number of narrative interviews which will form the final chapter of my analysis and led a seminar series on Tuesday nights for members of the Sijal Community. The seminar series which focused on political (mis)use of archives, archival imagination and memory activism was a fantastic opportunity for me to re-engage with the theories at the heart of my doctoral project. The papers and theories that have already inspired much theoretical musings took on a new meaning by being discussed with individuals working across different disciplines and different geographic backgrounds. Within the seminar series, I was also able to host a screening of the beautiful film “Soil and the Sea” which provides a new way in which to engage with the stories of the disappeared from the Lebanese Civil War. The producer Yara el-Murr joined for the discussion after the screening and it was fantastic to see how attendees were so affected by the film.

It really has been a wonderful but incredibly intensive three months in Amman and I truly am grateful for all those who made it possible. The city itself has been busy with both Palestine Film Week and Amman Film Festival. There really is something special about being immersed in the language so intensely and having the easy access of watching films in Arabic. In having the financial support to allow not needing to work part-time, I was also able to enjoy attending a fantastic “social and political life of portrait photography” at the wonderful Darkroom Studio Amman!

I’m looking forward to full-time thesis writing from September and taking the time to fully memorize all the vocabulary of the summer, but then to continue my Arabic studies! My first ever Arabic teacher always said “Arabic is a life long journey so you must be patient” – this part of the journey has been so enriching and beautiful (and extremely tiring) but I am beyond grateful.

Would you also like to benefit from our Travel Grants? Our applications are open all year! Find out more about the application procedure and criteria here

'Sometimes all it takes is to get over your fears to go and discover opportunities outside of your comfort zone.'

Would you also like to benefit from our Travel Grants? Our applications are open all year! Find out more about the application procedure and criteria here

Looking back at my time in Bahrain, I can honestly say it was one of the most eye-opening experiences of my life. Going there for my Honours Internship felt like stepping into a whole new world—familiar through our shared Arab identity, yet refreshingly different in culture, lifestyle, and perspectives.

I completed my internship at Arabian Gulf University in Manama, focusing on endometriosis, a gynecological condition affecting roughly 10% of women worldwide. My research involved working with organoid models, which are 3D cell cultures that maintain tissue complexity and provide a more accurate representation than traditional 2D models. Specifically, I explored how morphological and growth differences among organoids relate to histological characteristics.

Being a registered student at AGU also allowed me to live on campus in a dorm, which added a whole new dimension to my experience. I got to participate in student activities and really immerse myself in student life in Bahrain, which made the cultural exchange even richer.

One of the most rewarding aspects of my stay was the cultural exchange. I met people from across the MENA region—Kuwait, Oman, Sudan, Tunisia, Saudi Arabia, and of course Bahrain. Being Moroccan, I’ve always connected with my Arab identity through my own culture, but meeting others showed me how diverse and multifaceted the Arab world truly is. We shared discussions about current regional issues, and I got to experience the richness of the Arabic language and its many dialects. I was immersed in Khaliji Arabic, while many Bahrainis were curious about Darija, Moroccan Arabic. It was fascinating to see this exchange of language and culture act as a bridge between us.

The support of the Lutfia Rabbani Foundation made this opportunity possible. Without their grant, I would not have been able to fully embrace this experience. Beyond the financial support, the Foundation’s encouragement and guidance gave me confidence to dive in and make the most of every moment. The Foundation also helped me broaden my professional network. I made both formal and informal contacts that I believe will be valuable in the future. These connections gave me insight into local perspectives and introduced me to opportunities in the Gulf that I had not seriously considered before. This experience has already influenced my future plans—I now see the Gulf as a place where I could pursue further academic or professional goals.

Most importantly, this journey gave me knowledge that goes beyond the classroom. I learned adaptability, how to engage with people from different backgrounds, and how to appreciate diversity within a shared identity. These are lessons I will carry with me in both my studies and my career.

Looking back, I honestly can say that going to Bahrain has been one of my best decisions I have made in my life. Sometimes all it takes is to get over your fears to go and discover opportunities outside of your comfort zone.

From Medical Student to Doctor: My Elective in Pediatric Medicine in Tangier, Morocco

My name is Loubna Harroui and until recently I was a medical student at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam. Born and raised in the Netherlands, I grew up with strong ties to Morocco, as my family is from there and I visit almost every year. When the opportunity came to complete my final elective abroad, it felt only natural to choose Morocco. Therefore, I decided to do my internship at the Centre International de Pédiatrie (CIP) in Tangier, a private pediatric clinic where I spent eight weeks working alongside local doctors. This internship was the last part of my studies, and it turned out to be one of the most valuable and memorable parts of my medical education that I will carry with me throughout my career.

The clinic works with an open-door system: no scheduled appointments, but instead an intake at the front desk where children are seen the same day. On average, we treated 40 to 60 patients per day, ranging from routine consultations to complex cases.

What impressed me most was the extraordinary variety of cases. Many were familiar from my training in the Netherlands, such as viral respiratory infections, asthma or gastroenteritis. But in Tangier I saw these conditions more often in their severe form. For example, dehydration was a daily reality. Due to the hot climate, socioeconomic challenges and sometimes delayed access to medical care, children arrived at the clinic severely dehydrated, often requiring intravenous rehydration. It was both confronting and educational to realize how context can determine the gravity of a disease that we in the Netherlands usually see in much milder stages.

Another striking difference was the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori. While in the Netherlands it is relatively uncommon in children, in Morocco it is endemic. I was surprised by the number of young patients who tested positive, often presenting with abdominal pain or anemia. This pushed me to study the local epidemiology and to understand better why some diseases play such a large role in one country while being less relevant in another.

What also stood out to me were the surgical procedures. Circumcision, for example, is a routine part of pediatric care in Morocco, performed frequently for cultural and religious reasons. In the Netherlands, circumcision is rarely performed in medical settings unless there is a clinical indication. At CIP, however, I had the chance to witness and assist in several circumcisions, which gave me valuable hands-on experience with a procedure that is far less common in Dutch pediatrics.

Besides the private clinic, I was also given the opportunity to spend time in the public hospital. The contrast could not have been greater. The clinic was modern, organized, and well-equipped, while the hospital had limited resources, overcrowded wards, and patients often from poorer, rural backgrounds. Here I saw children suffering from trauma after traffic accidents, complex infections, and acute surgical problems that required immediate intervention. The difference between the two settings offered me a sharp lesson in health inequalities – both within Morocco itself and in comparison to the Netherlands.

My time in Tangier was not only about medicine. It was also about communication, culture, and connection. Explaining preventive measures to parents, often across language barriers, required patience and creativity. I learned how to build trust quickly, how to reassure anxious families, and how to adapt my explanations to different cultural contexts. These communication skills, I realized, are as essential to good medicine as any clinical knowledge.

Looking back, I am grateful for the chance to combine my academic training in Amsterdam with my cultural roots in Morocco. The elective gave me a deeper understanding of global pediatrics, showed me the importance of adapting care to local realities, and reminded me of the universal challenges and joys of working with children and their families.

This was not just the end of an internship; it was the closing chapter of my medical studies. With this experience in Tangier, I have officially completed my program and can proudly say that I am now a doctor. Returning to the Netherlands as a recently graduated doctor, I carry with me medical knowledge, cultural insights, and a stronger motivation to dedicate myself to the health of patients from all backgrounds.

Would you also like to benefit from our Travel Grants? Our applications are open all year! Find out more about the application procedure and criteria here

Sabeeh’s Reflections

We are proud to introduce Sabeeh Al-Khayyat, our 2024 – 2025 Leiden University Fund – Lutfia Rabbani Foundation Scholar. In this blog post, Sabeeh shares his personal reflections on his time in the Netherlands, offering insight into his academic journey, cultural experiences, and life as an international student. His story captures the spirit of curiosity, determination, and growth that defines the scholar experience.

As I enter the final stages of my degree, and in particular, the final stages of writing my thesis, I find myself reflecting almost daily on the journey that led me to this point. And so, I wanted to share these thoughts with the wider Lutfia Rabbani Foundation family, which has been my foundation (excuse the pun) throughout these last few months.

As I write these words from Amman, where I have returned to attend my younger brother’s high school graduation, I think back to my own graduation from school almost a decade ago. It reminded me of a younger version of myself; an idealist and an optimist with grand ideas of making the world a better place. In some ways, those parts of me have not changed at all. At the same time, harsh realities all around us have made it difficult to cling to that youthful hopefulness. Nonetheless, I do my best to hold on to my optimism. When I wake up in the morning, I remind myself why I am here—to earn my degree and be able to benefit those in my community, and beyond, who need it the most.

Notwithstanding the occasional challenges, this year has been filled with unforgettable highs. I have lovely memories from cycling up to Scheveningen (which still remains the singular Dutch word I can confidently say that I can correctly pronounce) whenever things have gotten a bit overwhelming. Indeed, it has been wonderful to experience the breathtaking natural beauty of the Netherlands this past year, even though I have only barely managed to scratch the surface!

If I may, at this juncture, give some advice to future scholars: while your programme will no doubt be your number one priority (I often joke that I am married to mine), make sure you take in all that this remarkable country has to offer, and immerse yourself in its culture.

You will find, not only that people appreciate it immensely when you try to embrace their culture, but also that the experience as a whole becomes much more rewarding.

Another standout moment from the past year was the privilege of being invited to speak at the MENA Trade Dinner. I still feel incredibly humbled by the overwhelmingly kind response to the short address I gave, and I will cherish the plethora of insightful discussions I had with many of the attendees that night. Yet another highlight was the pleasure of attending the signing of the renewal of the Leiden University Fund – Lutfia Rabbani Foundation scholarship agreement. Being a part of celebrating the partnership between the Fund, the Foundation and the University was a truly special moment.

And it made me think about the role that scholarships have played in shaping my own educational career. I still remember arriving to a new school in Amman in the winter of 2005 (my first time seeing snow!)—having moved with my family from warm Sharjah—and sitting entrance exams in Arabic, English and mathematics. Those entrance exams earned me not only a spot at the school, but also a scholarship, which, through my academic performance, I was able to extend year after year.

After I graduated school, another scholarship opened the door for me to attend the University of Leeds to complete a bachelor’s degree in law. That was a truly life-changing experience. At Leeds, I had the privilege of being taught by an alumna of the same programme I am now almost about to complete, and—bringing the journey full circle—the person who wrote my recommendation letter for this scholarship!

This is all to say that I could not have made it to where I am today without the kindness and generosity of so many. I am deeply indebted to everyone who has helped me advance my education. Among that long list, no doubt, are my parents, who have constantly strived to put mine and my siblings’ education above all else. Thank you.

On a final note, I wish to share a quote by the late King Hussein, who once said that

“peace comes from understanding”—a result that can only be furthered by the twin catalysts of education and cultural exchange.

Christina de Korte in Egypt

Would you also like to benefit from our Travel Grants? Our applications are open all year! Find out more about the application procedure and criteria here

In 2022 I came to Egypt for the first time to follow the Middle Eastern Bachelor Program at the Netherlands Flemish Language Institute in Cairo (NVIC). After completing my studies at the NVIC, I stayed in Egypt for four more months to dive into local techniques and work as an artist in residence. I kept finding a typical Egyptian textile that was asking for my attention, namely khayamiya. Khayamiya – derived from the Arabic word for tent, namely khayma – is an appliqué technique, predominantly used for making big handmade tents. Nowadays, tents made of khayamiya are still used for different purposes, for example, during events such as weddings and funerals, or iftars during Ramadan. The technique is also used on a smaller scale for objects such as pillow covers, and can be created through other means, such as machine-sewn or (digitally) printed.

From January 2025 until the beginning of May 2025 I returned to Egypt to conduct research for my research master’s thesis Let the Textile Speak: Egyptian Khayamiya Through the Streets of Cairo. Through the support of the travel grant of the Lutfia Rabbani Foundation, I was able to cover my travel costs to Egypt, but also the travel expenses during my stay. In this research, I focus on Egyptian khayamiya and its contemporary usages before and during Ramadan. By following the routes of various types of khayamiya through Cairo’s streets and taking courses in the Street of the Tentmakers to learn the technique, I analyse how khayamiya dresses up the city, and invites people to interact with it. This interdisciplinary approach between textiles, heritage, material religion, and (art-)history makes it possible to let the textile speak.

In addition to delving into collecting the data for my research, I was able to take my Egyptian-Arabic to another level since most of my respondents were Arabic speakers. Although my Arabic is not fluent, I was able to talk with many tentmakers, farrashin (the people who rent and build the tents), and other people related to khayamiya. In my experience, Egyptians create a very welcoming environment to learn Arabic, since the majority of people are extremely patient and willing to help.

It was an unforgettable experience to be in Egypt while seeing the preparations for Ramadan and the whole month of Ramadan. My enthusiasm for Egypt and khayamiya is not finished after this research period in Cairo, and I hope to return soon to extend this research by looking at the other usages of the textile that I encountered. During my stay, I was able to give two lectures and a workshop at the NVIC where I was working as a guest researcher. In the coming period, I will continue with these activities in the Netherlands on different occasions to share what I learned in the Street of the Tentmakers from my khayamiya teacher Ahmed, and share my enthusiasm for khayamiya and Egypt!

Marieke Den Ouden in Morocco

Image 7: Photo by: Chuan-Yun, Hsieh. Visiting the Mothership in Tanger. All other images by Marieke den Ouden in Taza and the surrounding.

Would you also like to benefit from our Travel Grants? Our applications are open all year! Find out more about the application procedure and criteria here

A different country, a different continent – I didn’t know where I would live for the next seven weeks, which family I’d stay with, what language would be spoken, how I should dress, or what exactly we would be doing.

Thanks to the Lutfia Rabbani Foundation, I had the freedom to fully prepare and embrace the unknown.

During my time in Morocco, I learned by living differently and by experiencing things in a new context. From Africa, I looked toward Europe; from within an Islamic culture, I reflected on a Christian and more secular society.

I also started thinking about migration, borders, and the quiet power of a passport – my passport – and the political decisions behind it. Why can I stay here without a visa for three months, while the same access isn’t granted to Moroccan citizens? I reflected on the value of money: who determines it? The fragility of promises and the risks of miscommunication came up often. Many of the places we visited had previously hosted foreign guests like us – people who offered hope for collaboration or a return visit, but who often couldn’t fulfill those expectations. This made me more cautious about what I said. And I became increasingly aware of our consumer behavior in the Netherlands.

For my art project, I specifically wanted to work beyond the classroom. That’s why I connected with Asmaa from Au Grain de Sésame, a social enterprise that develops innovative, sustainable products in collaboration with local craftswomen. She trains women to become financially independent. Asmaa was a valuable partner in this new country and unfamiliar culture. Asmaa’s work – combining craft, innovation, and economic independence – was truly inspiring.

I realized how challenging it is to work as a designer in a post-colonial context. What is appropriate? What is the unspoken visual language? And how do you collaborate on equal footing?

This experience shaped my way of thinking. It helped me understand how art can be a powerful tool for education and dialogue. Going beyond borders and embracing discomfort became an invitation to challenge myself, broaden my perspective, and connect deeply with others across cultures.

'Jordan has astounding natural beauty. Wadi Rum truly looks like Mars. And you can really float in the Dead Sea. It is not a marketing story.'

Would you also like to benefit from our Travel Grants? Our applications are open all year! Find out more about the application procedure and criteria here

Living and working in Jordan has been a rewarding experience so far. I have been here now for a month and a half. I live in Jabal Al-Weibdeh, Amman’s artistic centre that houses many other expats as well. My first month here was during Ramadan. During this holy month of fasting, Jordanians tended to evade the streets while the sun was out. Each day after sundown, restaurants were stacked, especially in the downtown area of the city, where tables were laid out with water and dates to break the fast. Although, I enjoyed the spiritual calm of these weeks, I was grateful for my internship to provide some business.

I work at the Al Quds Center for Political Studies, a small thinktank ran by Palestinian Jordanians. Through the countless conversations with my colleagues, I learned a great deal on Jordanian politics and the ins and outs of the region’s international relations. I also became more aware of the dynamics of the Israeli Palestinian conflict and the ongoing Gaza War. So far, I worked on the Center’s fundraising, communications and administration. The Center also hosts frequent workshops on timely issues in the MENA’s politics. A few weeks ago, the workshop was about Syria’s new regime and how it deals with the country’s minorities. Recently, I gave a presentation on political participation of youth in the Netherlands at the Center. The presentation was attended by many politically active Jordanian youth and it was illuminating to hear about their experiences engaging in Jordanian politics.

During the weekends, I often went to see the country’s many highlights. Jordan has astounding natural beauty. Wadi Rum truly looks like Mars. And you can really float in the Dead Sea. It is not a marketing story. And Petra is a must-see, that will leave anyone who exists the mountain city wondering: ‘How did they build this place?’

'My six weeks in Oman were a transformative experience... [it] broadened my clinical skills but also enriched my understanding of cultural diversity in healthcare'.

Would you also like to benefit from our Travel Grants? Our applications are open all year! Find out more about the application procedure and criteria here

From November 11th to December 20th, 2024, I had the privilege of completing a six-week elective in the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics at Sultan Qaboos University Hospital (SQUH) in Muscat, Oman. This experience offered me the opportunity to step outside the familiar Dutch healthcare system and immerse myself in the medical practices and cultural norms of the Middle East. My aim was to gain clinical experience in a well-developed healthcare setting while also deepening my understanding of the cultural and social aspects that influence patient care in this region.

The clinical aspect of my elective was both challenging and rewarding. At SQUH, I was actively involved in various departments, including the emergency gynecology unit, operating theaters, labor wards, and outpatient clinics. My daily activities included preparing patient cases, conducting physical examinations, assisting in surgeries, and contributing to treatment plans under the supervision of specialists. The structured healthcare system, inspired by the British model, provided a unique learning environment.

The hospital environment reflected a strong blend of modernity and tradition. Most healthcare professionals were highly trained, with many having completed part of their education in countries like the UK or Canada. However, cultural and religious values played a significant role in patient care. For instance, male gynecologists were rarely involved in physical examinations or deliveries due to cultural norms, and consent from patients or their families was essential for their involvement.

Language was another important aspect of my experience. While English was the primary language among staff, Arabic was often used with patients. My ability to understand and speak Arabic greatly enhanced my interactions with patients and colleagues, allowing me to build trust and communicate more effectively.

Living in Oman was a cultural adventure. I stayed at the Sultan Qaboos University off-campus residence, which was well-maintained and conveniently located. The facilities were excellent, and the staff ensured a comfortable stay for all international students.

Exploring Oman during my free time was an unforgettable experience. The natural beauty of the country, with its majestic mountains, pristine beaches, and vast deserts, was breathtaking.

Adapting to the cultural norms and healthcare environment required some adjustment. Gender segregation was noticeable in some areas, such as the hospital cafeteria and certain university spaces. Additionally, the dress code for women, which included wearing an abaya or a long coat, was different from what I was accustomed to in the Netherlands.

From a professional perspective, there was a strong emphasis on preparation and active participation. Morning rounds often included in-depth questioning by consultants, which motivated me to study hospital protocols and guidelines in detail. This expectation, while challenging, greatly enhanced my medical knowledge and confidence.

My six weeks in Oman were a transformative experience. The elective not only broadened my clinical skills but also enriched my understanding of cultural diversity in healthcare. I left with a deeper appreciation for the integration of modern medical practices and traditional values, and the experience strengthened my adaptability as a future physician.

I would highly recommend this elective to any medical student seeking a combination of professional growth, cultural immersion, and personal development